Responsible design is key to overcome privacy risks and explore the technology’s full potential

1 Introduction

When the Lumière brothers showed the first movie ever in 1895, the audience, not knowing what a “movie” was, was scared that the train showed in motion on the screen would enter the room. Soon, we will be sitting in this virtual train in virtual reality instead of just going to the cinema (McQuire, 1998). The world is changing rapidly and and the future of it is uncertain, feared and hardly predictable.

Most major problems the world is facing today are global. Locally we are almost impotent against the course of massive problems. The insecurity this creates is often more of a driver for innovation than striving for a better future is. A big task of innovation management is to locally tackle problems that were created on a global scale, as well as to reduce individual fears of the uncertain future. Until now, the public is mostly served with standardised public services and put into a passive role. (Baumann, 2007) The rapid development of information technologies has empowered individuals to actively participate in shaping the world. It is important to listen to the public, understand their needs and use this information for designing the future. Looking inside and understanding the social networks of interaction and communication gives valuable insights on what the problems are and how to tackle them. This should feed into decisions of the bodies shaping our future lives and societies. (Simmons & Brennan, 2013; Design Commission, 2014)

Thanks to technological progress, things in our environments create their own networks, interacting with human networks or taking active roles in them (Internet of Things). Human and technological actors are inseparable (Actor-Network-Theory) (Latour, 2005). Interactions and interdependencies in the expansive webs are invisible, but big amounts of data are created every second, helping to find innovation ideas and supporting management decisions when properly analysed. Intelligent analysis is an important challenge, as the data can help to identify and tackle problems in an early stage, but can also be misleading if over-interpreted. (Silver, 2012)

With the rapid development and expansion of digital networks and the disclosure of network data a big question of privacy arises. We passed from a modern, disciplinary society into a post-modern control society. Information is empowering governments and global forces to control individuals in any stage of their live (Deleuze, 1992). We are at a stage where it is upon us to decide on how much private information is needed to improve the quality of societies and community lives. A limit needs to be set before the world turns into an over-serviced space ship, as the dystopian future in Disney’s Wall-E tells (Murrey & Heumann, 2009). The challenge posed by the continuous implementation of technology will be to be able to set ethical limits to new developments as well as to provide tools for progress. (World Economic Forum, 2015)

In the first part of this work the literature review introduces the context to which this essay correlates and identifies the fear of an uncertain future as a driver for innovations. Roles and methods of social design and complaint management are presented as tools to identify problems and manage innovations in a public context. Throughout the media a trend towards the introduction of the internet of things can be detected. The literature review gives a state-of-the-art introduction to technological developments in that field, as well as its direct reference to the Actor-Network-Theory. At the end of the first part contemporary nascent privacy concerns in the context of post-modern control societies are outlined.

The second part of the essay consists of three practical examples from internet of things and sensor web technologies that were purposely developed to fulfil social demands, but include privacy concerns. The MK:Smart MotionMap is a public project in the city of Milton Keynes. An open data base on real-time traffic information in both pedestrian and motorised areas is to be provided. The project is not released yet, but privacy concerns are involved in the decision on how to design the data collection. If it is purely automated through sensors installed in the city the most accurate data can be collected, but individuals feel their privacy intruded if they are being captured on every step they take. If a model of active user participation is chosen, where only people willing to participate are entering data, the project might not reach the necessary number of participants to provide useful data.

IMRSV Cara Emotion Measurement is a software to equip every webcam with the ability to collect demographic data as well as emotions of people looking into it. It is used to provide adaptive advertising content in real life to target customers and show them products they are supposedly interested in. The software is by design not equipped with the ability to recognise faces, nor are any images or videos saved. Nevertheless public acceptance is low and privacy concerns are not arbitrary.

GiraffPlus was a two year pilot project of building a smart home, supporting elderly people to live at home alone and reducing the risks this encompasses. The problem of ageing population and an excess of demand for home-care in many countries could be solved by installing sensors throughout the home, signalling unusual events and behaviour. Additionally a robot-like device was given to the test persons, that allowed caregivers and relatives to visit the elderly virtually and check the conditions. Initial privacy concerns and fears of the new technology were not a big issue throughout the project as the devices were not perceived as intrusive and autonomous or uncontrollable. The conclusion draws insights from the literature review and the practical examples on how to build trust in systems that collect private data and the Internet of Things, to exploit its full potential. Some concerns will still remain, even if the products and services are designed to deal with data in a responsible and ethical way.

2 Literature Review

2.1 How the Uncertain Future is a Driver for Innovation

The future of the rapidly changing world is uncertain. Global risks can have far-reaching, cascading effects and cannot be described in isolation from each other, as they are interconnected. Uncertainties are various in their dimensions and characteristics and there is a lack of understanding on how to deal with them (Walker et al., 2003, p. 5). The Global Risk Report, published by the World Economic Forum (2015) since 10 years, builds upon the increasing connectedness of the world and calls for global cooperation to tackle foreseeable global risks. (World Economic Forum, 2015, pp. 9-10)

Globalisation and the liberalisation of markets lifted the power which is controlling our lives from a local, political level to a global level. Power is might and might is right, and can bypass international law. Though deregulation can in some cases make systems more flexible and less prone for catastrophic events, not all rules from society should be removed (Taleb, 2013, p. 120). Latecomers to modernity have to find local solutions to globally produced problems. Most societies are not able to decide about their own course anymore, as most fundamental problems are global and were created on a planetary scale. Social life changes by taking action to release societies from its fears, but the relentless global changes are not influenced by these actions locally taken. This impotence creates insecurity, which in turn enforces our fears. Personal fears about the uncertain future are exploited commercially and politically. The role of the state has changed from providing social security to servicing personal safety which makes the legitimisation of the political body questionable. (Baumann, 2007)

Individualism stands against the society, which is no longer protected. Moral issues arise within societies, as social and cultural boundaries coincide less and less closely. For example, the original purpose of building cities was the protection from outside dangers, today they themselves are associated with danger. A disintegration is taking place, as homes and urban infrastructures are build to protect individuals instead of connecting people to a community. The new “elite” class settles locally but is globally oriented and does not engage with local communities. (Baumann, 2007)

Local governments need to respond to the arising social issues with new approaches. According to Murray (2009) incremental improvements are not enough, but a radical social innovation is necessary to counterattack pressing critical topics. In the UK, growing social pressures are opposed to the reduction of public spending. Creation of new resources is neither possible nor necessary, but the radical innovation of existing ones is required.

Carlota Perez (2009) raises hopes that these years of intense institutional recompositions, initialised by the information-technological revolution and the financial crash in the previous decade, are a steppingstone to a golden age. New forms of organisations and regulations provide a patch for the technology to spread into public and private sectors, triggering intense innovation. To make full use of the emerging possibilities it is fundamental that well established industries and organisations implement new technologies to spread the gains more widely and reach a new social settlement.

2.2 Social Design

Knowledge of today is not valid tomorrow, what is stable is wisdom and flexibility in the ever changing environments. Long-term thinking and planning is obsolete, as forgetting of “old” standards can be important for the next success (Baumann, 2007). Stable systems are fragile, as unpredictable events have much more severe consequences to them than to variable systems (Taleb, 2013, p. 85).

Public authorities make believe that they are able to create a utopia, a world we can trust in, with as little unknown variables as possible and eliminating individual fears. We are well aware that we cannot protect ourselves from catastrophes, but exactly this fear gives us a thrive to create a safer world. This implies our efforts for innovation are rather driven by fear than by our dream of creating a great future (Baumann, 2007). The traditional form of risk management considers only events as risks that negatively hit us in the past, but leaves out that in the past, before the catastrophe had happened, the happening had never been considered and was most likely unpredictable (Taleb, 2013, p.334). Building resilience against global risks has been identified as an important task by the World Economic Forum (2015, p. 9), which is difficult to exercise in practice. One possible approach to this mission is an emerging new “social economy”, one that is not based on production and consumption of commodities. Widely distributed communication networks are intensively used to hold relationships. Production and consumption are not strictly separated as collaboration and repeated interaction gain in importance. Values and missions have a more important role than ever. This economy can mainly be found in areas where public sector, NPOs and the commercial markets overlap. This economy could be the main actor in solving globally created problems, but it lacks capital and demand. Only few of the initiatives started in this economy have grown to scale. (Murray, 2009)

Taleb (2013, p. 131) argues that many problems and fears we are facing are often mistaken as risk. Complaints are connected with negative thoughts and we tend to respond to it promptly to get it off the table. Instead, when people find it worth complaining, it shows that they had an initial expectation and demand that has not been met. This gap leaves room for improvement and innovation. With the increasing use of new information technologies our way of complaining changes. Technological development increases expectations towards services in general, and together with the facilitation of communication feedback is given much easier. The collected data, when systematically analysed, provides valuable insight and knowledge to be used by social designers to design tools to change the culture of service-delivery and meet the needs of societies. (Simmons & Brennan, 2013)

At the moment, the public is put into a passive role, serviced with standardised public services which are based on a post-war understanding of how to manage delivery by meeting targets and centralised control. With the changing communication patterns also services need to change and be citizen centred (Simmons & Brennan, 2013). Public services in the UK are slowly beginning to open up to the public. Citizens are invited to collaborate, choose, diversify and provide data. This open public services agenda is mainly driven by digitisation and big data. (Design Commission, 2014)

Albeit, big data is useless without design. The Design Commission (2014) points out that young designers now are not necessarily being taught how to use data. In the private sector only some design studios start to focus on technology and the use of big data. The new social design should be led by the government and is required to apply creative problem solving processes to social problems. A user focussed design approach to the implementation of new technologies is important to make sure, that technology does not complicate our lives and does not introduce unnatural elements into our daily lives. Technology is at its best when it is invisible and naturally integrates into our behaviour (Taleb, 2013, p. 315). The Internet of Things brings together the interface of physical objects and digital information. It is predicted to be surrounding us evermore in the future and looks promising to create smarter cities and communities. (Design Commission, 2014; Gartner, 2014)

2.3 The Internet of Things and the Actor-Network-Theory

The internet in its original sense was fully dependent on content created by humans. As humans have limited resources in capturing accurate data about the real world, the internet knows a lot about ideas, but little about things. Kevin Ashton (2009) points out the importance to empower computers with their own means to gather information about the world and the things in it to eliminate the limitations of human-entered data. The Internet of Things has a huge potential for innovations on simplifying our lives and overcoming social problems.

Gartner (2014) predicts big investments in smart infrastructure in 2015. Objects will create networks around us and will be of significant public value to make our environments smarter. Google chairman Eric Schmidt predicted at the World Economic Forum in Davos (2015) that the internet as we know it will disappear. It will be surrounding us all the time and will connect us with all the objects that we are interacting with, as well as the connected objects themselves will communicate with each other. (Szalai, 2015; World Economic Forum, 2015)

A lot of things like society, economy, markets and cultural behaviour are man made, but grow and reach some kind of self organisation. They replicate biological, complex systems. The internet has developed such a self organised complexity, and is getting even more complex when including things as actors. In complex systems interdependencies are severe and causes for afflictions cannot really be detected or defined (Taleb, 2013, p. 56). Simple systems, like mechanical devices, are not linked into a dynamic network. One mistake reduces the risk of it happening again, as learning from mistakes leads to future improvements. Mistakes in complex systems instead make the next one even more likely to happen as they are linked in a dense network of actors, with far reaching effects (Taleb, 2013, p. 73).

The Actor-Network-Theory is a social theory treating objects as part of social networks. It explains what it takes to think and act and how networks reveal around every single subject, human or non-human. It has often been perceived controversial as it sets non-human actors on the same stage with humans, but with the emergence of the Internet of Things, many critics’ points are not supportable anymore and the theory gains new importance (Latour, 2005, pp. 131-132). There can be no actor without network and no network without actors. To define an actor, and what it is that is necessary to exist, you also have to define it’s network which helps to distribute and reallocate the actor’s actions. Our contemporary networks are socially an technically determined. Technical development is influenced by socio cultural backgrounds, as well as technology influences societies. (Latour, 2005)

Tomas Saraceno, 14 Billions (2010)

Tomas Saraceno, 14 Billions (2010)The artist Thomas Saraceno (2010) references to networks in his work 14 Billions. He uses the structure of a spider web to describe how a network is, when its actors are closely enough knitted, not different from a cloth. If there are enough actors involved, a network can be universal. Spheres, dense networks, are fully localisable, and by putting work into a room you see that a sphere itself cannot exist without being connected to other spheres. Spheres themselves become actors in overriding networks (Latour, 2011). The work rethinks our relationship to one another and the cultural structures of ownership and nationality. It questions the stability and structure of man made environments. (Sommariva, 2010)

In a network, individuality is dissolved among social affairs. Statistics focus as little on individuals as possible, not considering that the whole cannot exist without it’s parts (actors and networks) and is therefore inferior than the individual actors. Technology, big data and statistics make it easy to navigate from individual level to the aggregate, and the two extreme points are loosing their privileges. Knowledge about interaction is lost, and although the internet has developed an almost natural self organisation, social sciences cannot imitate natural sciences. (Latour, 2005)

The massive amount of statistics and data that is created every minute needs to be managed, a challenge that we are struggling to tackle. Big data makes us believe that the future will get more and more predictable and therefore less uncertain, so we can reduce our fears. However, too much data makes our view fuzzy and the future less predictable than ever. More data means more information, but at the same time more false information. We tend to listen to every noise, slight deviations to normality, and try to predict a catastrophe, and while focussing on that we might ignore the signal of the really big event. (Silver, 2012; Taleb, 2013, p. 307)

Hyper-connectivity, physical objects being connected to the internet and the constant feed of sensitive personal data being stored and connected in invisible but massive networks, entails new risks. The analytics of various data sources can deliver breakthrough insights for innovations but also rises concerns about the responsible use of private data. All the data points together could be used to create a comprehensive representation of every single subjects actions and intentions, not only online but increasingly also in the real world. (World Economic Forum, 2015, p. 22)

2.4 Privacy in a Control Society

Privacy and security will be the key concerns for individuals, when smart objects around them collect sensitive, private information. Exposures about data fraud, leaks and cyber espionage have eroded general trust. The development of rules for the interaction of smart objects will take many years, so will the creation of trust. (Gartner, 2014; World Economic Forum, 2015, p. 10)

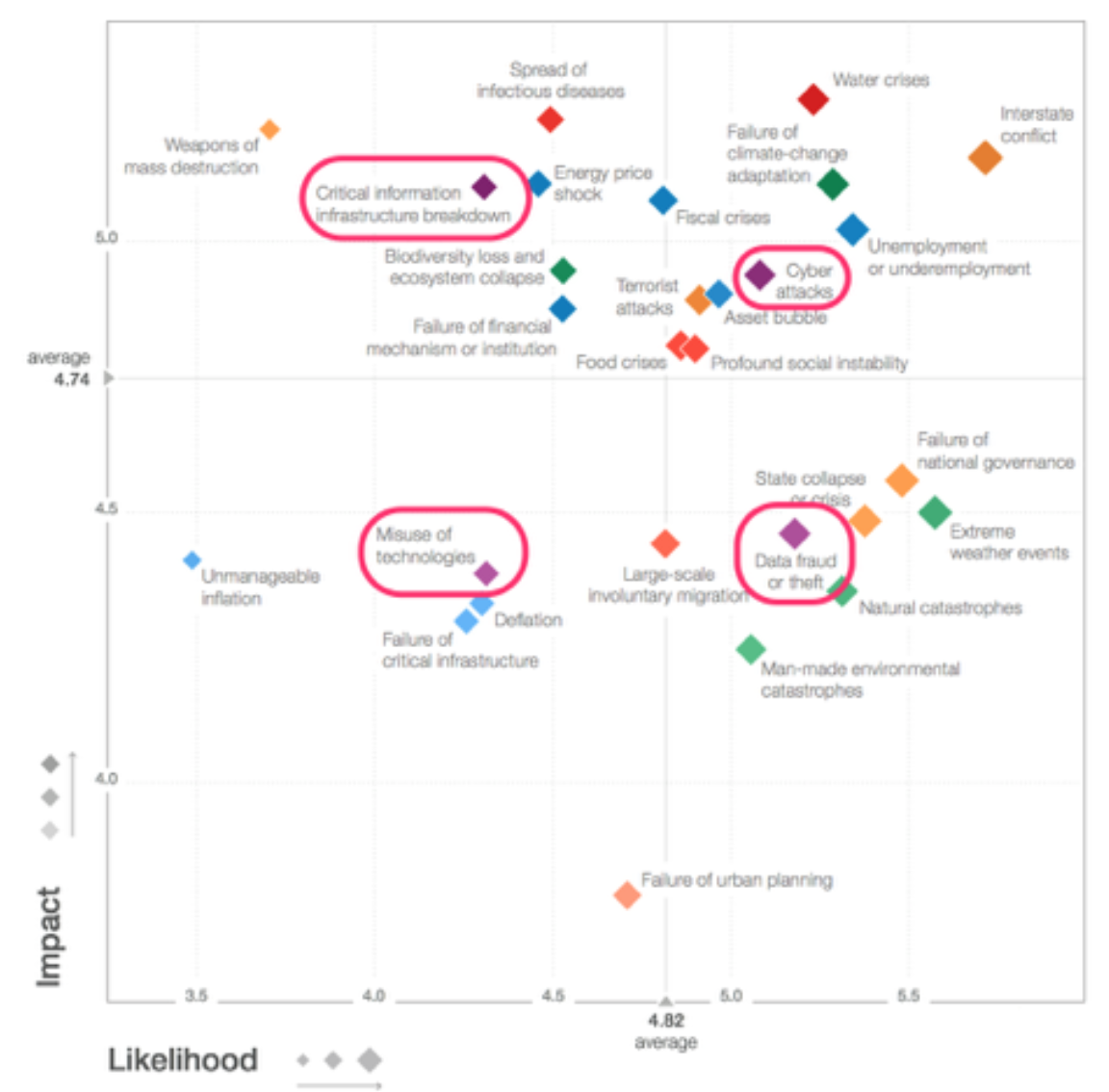

The Global Risks Landscape, WEF (2015)

The Global Risks Landscape, WEF (2015)Four of the global risks identified by the World Economic Forum 2015 in Davos are of technological nature, with data fraud or theft and cyber attacks within the top ten risks most likely to happen. By definition, “a global risk is an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, can cause significant negative impact for several countries or industries within the next 10 years.” (World Economic Forum, 2015, p. 9)

The internet as we know it has been developed without big security concerns until now. “The Internet of Things is very likely to disrupt business models and ecosystems across a range of industries.” (World Economic Forum, 2015, p. 22) Its innovations will bring positive changes as well as many risks and major public security failure could prevent the huge potential of the Internet of things to become widespread. (World Economic Forum, 2015, p. 22)

The new “everywhere internet” is developing towards a huge, invasive apparatus, monitoring and analysing us at every moment in our lives to package up every existence into a data bundle and use it for marketing purposes. In our control society marketing shifts to the centre of each organisation, trying to sell us the soul of an non-human entity. The operations in the markets is used as an instrument of social control (Deleuze, 1992). Though, the positive aspects this new technology can bring us for now still outweigh the restrictions on privacy. (Lomas, 2015)

Deleuze (1992) described at the end of the last century a social transformation from a disciplinary to a control society that we are undergoing. In disciplinary societies as described by Foucault (1977) individuals passed from one closed environment to another. Today, these organisations are not closed anymore but connected with each other and control is free floating. Individuals rival against each other within organisations and the masses are aggregated to numbers, stored in data banks. We ourselves built and contributed to this control systems to control each other. The new technologies that come with - or drive - the transformation to control societies model the world and dangers of entropy and sabotage, that we are facing now, arise.

3 Practical Examples

3.1 MK:Smart MotionMap

Milton Keynes is a fast growing city north of London. A major challenge the city faces is to support sustainable growth without exceeding the capacity of the existing infrastructure. The initiative MK:Smart is a collaboration between private and public organisations, led by The Open University, developing innovative solutions to support economic growth in Milton Keynes. In the centre of the project stands the “MK Data Hub”, a database of information from different data sources - including data from key infrastructure and sensor networks, as well as the implementation of a city-wide Internet of Things network. The goal is to build a smart city system, enabling active, participatory co-creation of value by citizens (MK:Smart, 2015; Valdez & Potter, 2014). Potential benefits offered by smart city systems can be realised only if the community accepts and embraces the systems, which need to actively facilitate everyday practices (Kitchin, 2014, pp. 11-12).

Milton Keynes is emerging as a leader in the field of intelligent mobility. The goal is to build an environment in which a variety of transport modes and systems can evolve and adapt to on-demand travel needs and the environment. Real time data from the MK Data Hub, driven by the individual needs of travellers, is the basis for innovations in public transport (Snelson on MK:Smart). The city MotionMap, a city-wide transport information platform, will collect and display real time movements of people and vehicles across the city, as well as estimations for traffic congestions and crowding (MK:Smart, 2015). MotionMap is not intended to be a product or service but rather a data platform. “The applications developed around MotionMap are expected to empower citizens to choose more sustainable transport behaviours.” The impact is expected to change behaviours of citizens, but also to allow the local authority to provide more sustainable and more efficient transport services. (Valdez in The Open University, 2014, pp. 71-72)

This pilot project is designed to provide insights and learning about the interrelations of technology, economy and society. Many socio-technical considerations need to be taken into account when designing a large scale urban sensing system. In early discussions with citizens it was revealed, that citizens do not entirely trust the system and it’s management. The inclusion of the private industry reduces the potential thread that the public sector is becoming omniscient and controlling through the urban sensing systems. Still, people fear that the private sector will collect data without respect of privacy and with the interest of monetising public services. The general feeling is that citizens bear the cost of smart technologies through sacrifices of privacy, while the gains will mainly benefit public and industrial actors. (Valdez Juarez & Potter, 2014) “The choices made in the design of the system will raise concerns about engagement, participation, privacy, ownership, control, technological surveillance and behaviour change in smart cities.” (Valdez in The Open University, 2014, p. 72)

Furthermore, the systems data requirement are raising questions, which role the people will take within the system. If people are supposed to remain passive, with sensors installed throughout the city collecting data, citizens may not even be aware of all the sensors watching them and tracking their private mobile devices. (Valdez in The Open University, 2014, p. 71)

To increase legitimacy and the perceived value of MotionMap, citizen will be given an active role for providing data as well as participation in the creation of new services, instead of providing centrally planned services, as the data received from sensors or active citizen participation will be stored in an open data hub, accessible for everyone. This approach brings challenges on its own as mobilising consumer participation is not an easy task. It is important that MotionMap provides value for car users, public transport users, pedestrians and cyclists alike. It is important that the right interfaces are designed through co-creation of the public and private sector. (Valdez Juarez & Potter, 2014)

Keerthi (2014) identified the benefits of promoting transparency and improving the projects reputation that the open data hub is supposed to bring to the users. Users are likely to find creative and innovative means for using their activity data to benefit themselves. However, the same study shows that privacy risks and challenges remain and might outweigh the benefits of accessible consumer activity data. People fear that the data could be misinterpreted by others looking at it, creating a bad reputation of an individual, especially if the individual could be re-identified. Another challenge is that by opening a secure gate to retrieve the data, there remains a perceived risk of data leakage and attacks. Additionally, users fear a breach of personal and organisational confidentiality, as well as third party exploitation of data which is not intended neither by users nor by the organisation. (Keerthi, 2014)

3.2 IMRSV - Cara Emotion Measurement

Nesta’s Head of Startups and New Technology Research Christopher Haley (2015) predicts for 2015 a trend for crowd-aware billboards. They will be able to sense demographics of the bypassing crowd and adapt its contents accordingly. “Currently, the leading-edge of targeted advertising is online but billboards are about to make a comeback, and blur the lines between ‘old’ and ‘new’ media.” (Haley, 2015) IMRSV developed a technology, called Cara, that turns any webcam into a sensor that captures and analyses facial expressions. It gathers anonymous real time data of general demographic insights such as gender, age, attention time and emotions by recognising smile, surprise, dislike etc. Cara can be used in setup environments like usability testing and product research, but as easy is it, to install it with a webcam in the “real world” and measure user engagement and reactions towards brands, products and advertising off-line. Also can it be used for interaction with computers, triggering events or specific content, depending on who and how many are interacting. (IMRSV, 2015)

The main idea behind Cara is, to provide enterprises with data and knowledge about their customers in the real world so they can personalise and adapt advertising based on demographics as it is already standard in online advertising. It is also supposed to add value to customers, who get to see things that interests them supposedly. (IMRSV, 2015) For example, a webcam is installed in the Reebok store in New York City at the wall of shoes, to identify which shoes are inspected by whom, to then promote different shoes to different types of customers. (Metz, 2013)

Privacy concerns in the public arise. The idea that a camera is taking a shot of your face while looking at billboards or products seems to include many privacy risks. In its privacy policy, IMRSV states that only the data from the image analysis is extracted and saved as a file, and cannot be traced back to identify individuals. By design it does not store, record or transmit any images or videos to secure privacy. The software is working with a anonymous video analytics technology and, in contrast to face recognition technologies, has no capability of knowing any personal identity (IMRSV, 2015).

Respecting privacy by design helps companies to avoid negative consequences that often go hand in hand wit data collection. Still might the system violate privacy. By identifying multiple variable like gender, age and eventually race, putting these categories into a system and using multiple cameras you could reasonably identify somebody and his returning behaviour. (Metz, 2013)

3.3 GiraffPlus

The project GiraffPlus encompasses a system for building smart homes, to enable elderly people to stay at home and remain independent even after a point where they usually would physically or mentally not be able to live alone anymore. A network of sensors in and around the home as well as directly on the body is installed, customised to the user’s and health care professionals’ needs. These sensors track the seniors’ activity pattern and when analysed, the data shows if something is out of the ordinary. In the centre of the project stands a robot, called Giraff, through which caregivers and relatives can virtually visit the elderly person at home. The service robot was created to help with caregiving, a task that humans are increasingly fail to meet demand for. (GiraffPlus, 2014)

The project shall address the concerns of isolation and safety elderly often have when living alone. Increased social contact through the robot actively contributes to longer independency and a better quality of life. Benefits for the caregiver include continuous information about the caretaker’s wellbeing, activity and potential illnesses or risks risks. The remote caregiving is more time efficient and thus cheaper. (GiraffPlus, 2014)

Robots and technological devices taking care of humans - at one point autonomous and without human interventions - is a future scenario that can be seen utopian as well as dystopian. On the positive side, it will help older people to be autonomous. On the contrary, their privacy will be invaded as they are monitored all the time. It is important to understand what the elderly expect, need and want from the caring system as it affects how they value its potential utility. (Frennert, 2013, p. 9-10) As ageing is a social construction without clear boundaries these expectations are changing as well. To tackle this problem, Frennet (2013, p. 75) suggests to involve different users thorough the product development process. This has been done at GiraffPlus.

The EU-funded project was running from January 2012 to December 2014. Several groups of elderly people in Italy, Spain and Sweden where part of the project. Input from the users was constantly evaluated to drive the further development of the system to meet the actual needs and capabilities. (GiraffPlus, 2014)

To overcome the non-acceptance of being monitored by a video camera and the fear of too much intrusion into privacy the Giraff remained purely human controlled rather than being an autonomous robot. It is a two way communication platform and can only move around if remotely controlled by a person via the internet. Furthermore, the technology behind the video conferencing application does not support recording of any kind. (Kirkpatrick, 2014)

Nonna Lea (Ralli, 2013), one of the test persons, writes on her blog about her experience with the robot. Initially she had concerns about being under surveillance all the time, with all her movements and actions recorded, but after some time she developed a “friendship” to the electronic companion and called him Mr. Robin. GiraffPlus helps her to stay independent as she decided to not live with her daughter. Also does she feel saver since she got the robot, as she knows that in case something happens people would notice.

4 Conclusion

Disclosures of data leakages and abuse of private data has left the individuals with a concern when it comes to sharing and saving private information into the big data. The Internet of Things with an important potential to solve some of the most pressing social issues might not be exploited to its fullest capabilities if the privacy concerns cannot be overcome by regulating data usage to a satisfactory extent.

“Privacy as we knew it in the past is no longer feasible. How we conventionally think of privacy is dead. We lead an enormous digital trail. […] laws surrounding privacy need to be laws about data and usage, not about the technology.” (Selzer in World Economic Forum, 2015)

From the literature review and the examples this essay features, some insights on how trust in the product or service can be obtained by applying responsible design rules can be drawn:

The cooperation of public and private sector organisations is more likely to be accepted, as the fear of a “big brother” state can be reduced. In any case it must be ensured that the main benefit is held by individuals and private data is not abused for unexpected marketing purposes by involved private companies. People should always be asked if they agree to provide some data or not, even if it is hard to activate a critical mass of individuals. If people are just passive part of the system they feel that the data was stolen from them. Active participation should also infringe on the product creation process. If the aggregate data is made public for individual use, even individuals find creative, innovative means to develop beneficial solutions. Open access to data also increases transparency of the whole project which in turn enforces trust. To activate and include people in the creation process well designed interfaces are a must. Identifying needs and expectations from the target users have to be identified and should later in the product or service development process be used as a benchmark if the technology is purposeful. Systems are perceived as of much higher value and trust in it is much higher if they are fulfilling expectations. Another important feature to ensure privacy is to make sure that re-identification of individuals is impossible. By design, recordings of any identifying features must be excluded from the technologies possibilities. The last identified insight is, that acceptance of technology is bigger, if the control remains in human hands and robotic actors do not take decisions for actions themselves.

Even if precautions are taken, some fears and concerns about personal privacy remain when it comes to the Internet of Things and sensory data collection. System leakages and data abuse as well as virtual attacks from third parties cannot completely be excluded once a system is opened up for public use. Furthermore, even if the technology itself has no features of identifying individuals, if a certain amount of demographic data is collected and put into a systematic order, re- identification can never be fully circumvented.

The Internet of Things will play an important role in our future societies. It will simplify our lives and help us to solve many issues we failed to solve until now. Privacy concerns about big data are legitimate, but it is also about us to create ethical standards on data usage.

References

Ashton, K. (2009) That “Internet of Things” Thing. RFID Journal [Internet], 22 June, Available from: http://

www.rfidjournal.com/articles/pdf?4986 [Accessed 28 January 2015].

Bauman, Z. (2007) Liquid Times. Living in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Deleuze, G. (1992) Postscript on the Societies of Control. October. vol. 59, pp. 3-7.

Design Commission (2014) Designing the Digital Economy: Embedding Growth through Design, Innovation

and Technology. London: Design Commission.

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York, Pantheon Books.

Frennert, S. (2013) Older People and the Adoption of Innovations: A study of the expectations on the use of

social assistive robots and telehealthcare systems . Lund: Lund University.

Gartner (2014) Top 10 Mobile Technologies and Capabilities for 2015 and 2016. [Internet], 12 February,

Available from: https://www.gartner.com/doc/2665315?ref=SiteSearch&refval=&pcp=mpe [Accessed 29 January 2015] Stamford: Gartner, Inc. and/or its Affiliates.

Haley, C. (2015) Crowd-aware billboards. Nesta [Internet], Available from: https://www.nesta.org.uk/news/

2015-predictions/crowd-aware-billboards [Accessed 1 February 2015].

IMRSV (2015) [Internet] Available from: https://www.imrsv.com/faq/cara-basics [Accessed 1 February 2015].

Keerthi, T. (2014) Privacy implications of online consumer-activity data: an empirical study. Second

Workshop on Society, Privacy and the Semantic Web - Policy and Technology [Internet], 20 October,

Available from: https://oro.open.ac.uk/41308/ [Accessed 31 January 2015].

Kirkpatrick, K. (2014) Sensors for Seniors. Communications of the ACM, vol. 57, pt. 12, pp. 17-19.

Kitchin, R. (2014) The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal. vol. 79, pt. 1, pp. 1-14.

Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to the Actor-Network-Theory. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Latour, B. (2011) Some Experiments in Art and Politics. e-flux journal. vol. 23 [Internet], March, Available

from: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/some-experiments-in-art-and-politics/ [Accessed 30 January 2015].

Lomas, N. (2015) What Happens To Privacy When The Internet Is In Everything? [Internet], 25 January,

Available from: https://techcrunch.com/2015/01/25/what-happens-to-privacy-when-the-internet-is-ineverything/? [Access 30 January 2015].

McQuire, S. (1998) Visions of modernity: representation, memory, time and space in the age of the camera.

London: Sage.

Metz, C. (2013) Computer Vision Invades Public Cameras to Track the People. Wired [Internet], 15 July,

Available from: https://www.wired.com/2013/07/caraplacemeter-google-glass/ [Accessed 1 February 2015].

MK:Smart (2015) [Internet] Available from: https://www.mksmart.org/ [Accessed 31 January 2015].

Murray, R. (2009) Danger and Opportunity. Crisis and the new social economy. London: Nesta.

Murray, R., Heumann, J. (2009) WALL-E: from environmental adaptation to sentimental nostalgia. Jump Cut:

A Review of Contemporary Media [Internet], vol. 51. Available from: https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/

jc51.2009/WallE/text.html [Accessed 2 February 2015].

Ralli L. M. (2013) Ecco Mister Robin. Nonna Lea, 1 December [Internet blog]. Available from: https://

nonnalea.wordpress.com/2013/12/01/ecco-mister-robin/ [Accessed 1 February 2015].

Perez, C. (2009) After Crisis: Creative Construction. Open Democracy [Internet], 5 March, Available from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/article/economics/email/how-to-make-economic-crisis-creative [Accessed 30 January 2015].

Simmons, R., Brennan, C. (2013) Grumbles, Gripes and Grievances. The Role of Complaints in Transforming Public Services. London: Nesta.

Sommariva, E. (2010) Tomás Saraceno 14 Billion (working title) at Baltic. [Internet], 22 July, Available from:

https://www.domusweb.it/en/news/2010/07/22/tomas-saraceno-14-billion-working-title-at-baltic.html [Accessed 29 January 2015].

Silver, N. (2012) The Signal and the Noise: The Art and Science of Prediction. London: Penguin Books.

Szalai, E. (2015) Google Chairman Eric Schmidt: "The Internet Will Disappear”. The Hollywood Reporter

[Internet], 22 January, Available from: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/google-chairman-ericschmidt-internet-765989 [Accessed 29 January 2015].

Taleb, N. N. (2013) Antifragile. Things that Gain from Disorder. London: Penguin Books.

Valdez Juarez, A.-M., Potter, S. (2014) Big data without Big Brother: emerging issues in smart transport in

Milton Keynes. Digital Economy All-Hands Conference 2014, Imperial College, London. [Internet], 3-5

December, Available from: https://oro.open.ac.uk/41925/ [Accessed 31 January 2015].

Valdez, A.-M. (2014) Urban sensing systems for behaviour change: Emerging issues in a smart transport

project in Milton Keynes, in The Open University (2014) ’Broadening the Scope’, 29 September, Milton

Keynes.

Walker, W.E., Harremoes, P., Rotmans, J., Van Der Sluijs, J.P., Van Asselt, M.B.A. (2003) Defining

Uncertainty. A Conceptual Basis for Uncertainty Management in Model-Based Decision Support. Integrated

Assessment. vol. 4, pt. 1, pp. 5-17.

World Economic Forum (2015) Global Risks Landscape 2015. Global Risks 2015. 10th ed. G Geneva: World Economic Forum.